Late September evening 2023 year. You lazily leaf through ebay. Among the usual junk comes across strange iron - heavy industrial modules. Siemens and Areva logos flaunts on boards. The description is scarce, But professional, The price is amazingly affordable.

Here are the components of the Teleperm XS system - a digital platform for controlling nuclear reactors. Right now, such equipment controls the safety of nuclear power plants around the world..

Independent security researcher Ruben Santamarta has been hacking everything from satellite terminals to voting systems for twenty years.. Seeing these lots, he couldn't pass by. I bought the components and wondered: what will happen, if an attacker gets to the “brains” of the reactor?

Today we will follow his path and simulate a realistic cyber attack. Scenario "Cyber"Three Mile Island», which, according to Santamarta's calculations, for 49 minutes leads to a meltdown of the reactor core.

The journey into the heart of a nuclear reactor begins.

Nuclear power plant like a giant samovar

To understand, how to hack a nuclear reactor, let's figure it out first, How it works. Let's not go into the jungle of neutron kinetics, basic principles and a few analogies will suffice.

Three contours

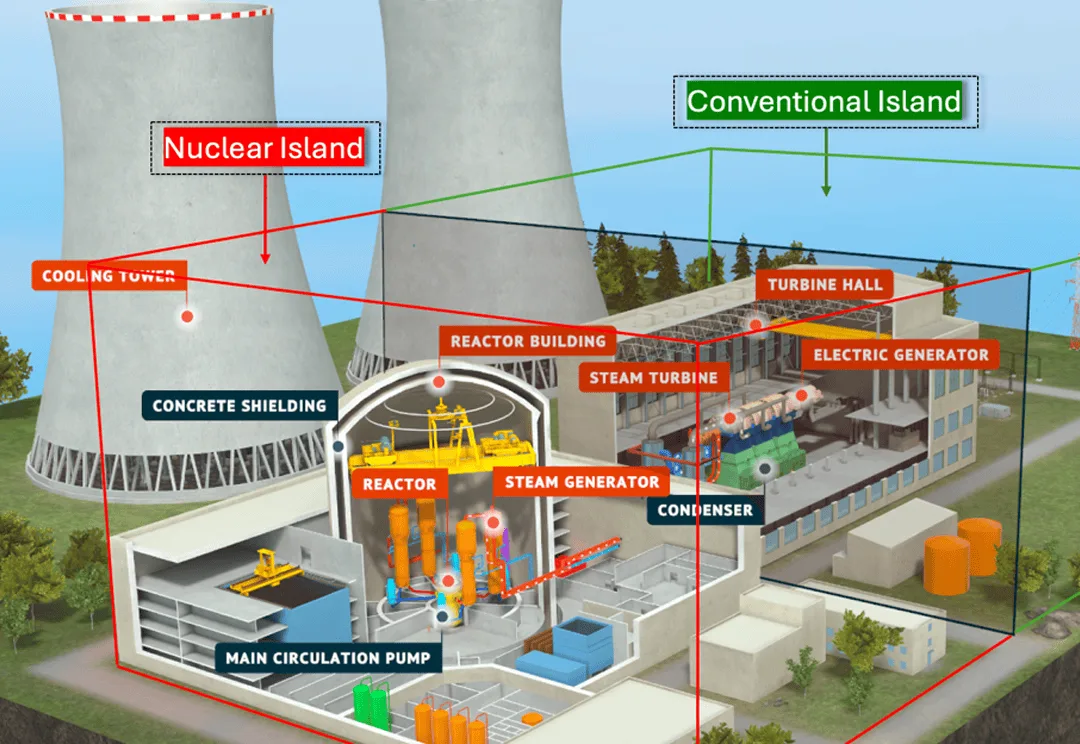

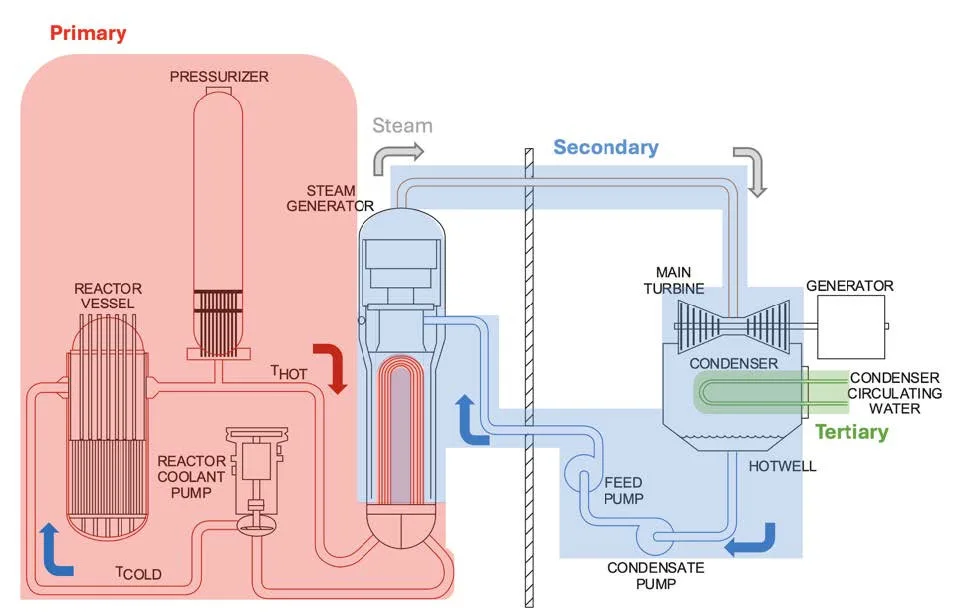

In fact, pressurized water nuclear reactor (PWR) - this is an incredibly complex and expensive boiler. Simplified, its design comes down to three circuits.

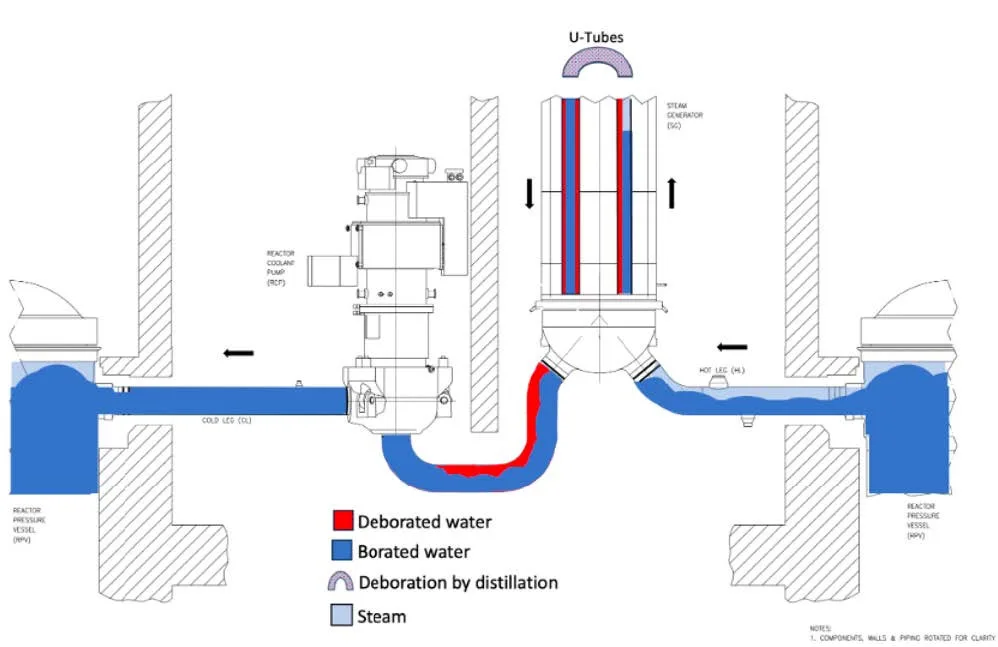

First circuit - the heart of the reactor. Fuel rods are contained within a durable steel housing, collected from uranium dioxide tablets. There's a chain reaction going on here, and a colossal amount of heat is released.

Water passes through the core and heats up to 330°C. So as not to boil, she is kept under pressure 155 atmosphere. This water is radioactive and never leaves the sealed area.

Second circuit already contains steam. Hot radioactive water from the primary circuit passes through a steam generator - a giant heat exchanger. She's inside him, without mixing, boils secondary circuit water. The resulting steam is no longer radioactive. It is this that is supplied through pipes to the turbine room and rotates the turbine.. The turbine turns the generator, generator provides current. But that's not all.

Third circuit responsible for cooling. The spent steam must be condensed back into water and sent to a new circle.. To do this, use water from a nearby pond., rivers or seas, which is driven through cooling towers.

Now, when the device was sorted out, Let's move on to physics - those nuances and the security system, which distinguish a reactor from an atomic bomb.

Reactivity

To keep the car moving, need to step on the gas. In a reactor, the “gas” is neutrons.. Their number determines the reproduction rate (). If

(negative reactivity) - slows down, we are slowing down. If

(criticality) — the reactor operates stably, like on cruise control, producing constant power.

The problem is, that almost all neutrons during fission are created instantly. Everything moves so quickly with them., that no control system has time to react. However, about 0,7% neutrons - delayed, they appear with a delay of up to several minutes. Thanks to this tiny fraction we have time to control the reactor.

But the most interesting thing is that the reactor has a built-in brake, or Doppler effect. The hotter the fuel gets, the more active uranium-238 absorbs neutrons, automatically slowing down the reaction. This is a fundamental law of physics, which cannot be turned off. In fact, this is the main fuse, but in addition to it there is a whole range of protective engineering solutions.

Nuclear reactor protection

The layered defense of the reactor is built on the principle of a medieval castle: ditch, outer wall, interior wall, citadel.

The first line of defense is the fuel pellet itself, which holds most of the fission products. The second is a sealed shell of the fuel rod made of a zirconium-tin alloy. Third - a durable steel reactor vessel. The fourth is a reinforced concrete hermetic shell (containment) more than a meter thick, able to withstand an airplane crash. Fifth line of defense - security systems and operators.

Simple idea: failure of one level should not lead to disaster. For trouble to happen, all the walls of the castle must collapse one by one.

A hypothetical hacker here is most interested in security systems and operators. Security systems continuously collect telemetry from thousands of sensors and process it in controllers using built-in voting logic. At the slightest deviation from the norm, they give commands to the actuators to shut down the reactor and start cooling. Then the operators start working: they have to manually perform the steps, provided for by the regulations, and bring the installation to a safe state.

So, we are dealing with a very complex device, designed like this, so that any failure leads to a safe stop. Now let's figure it out, how the Teleperm XS platform works.

Teleperm XS. Anatomy of nuclear brains

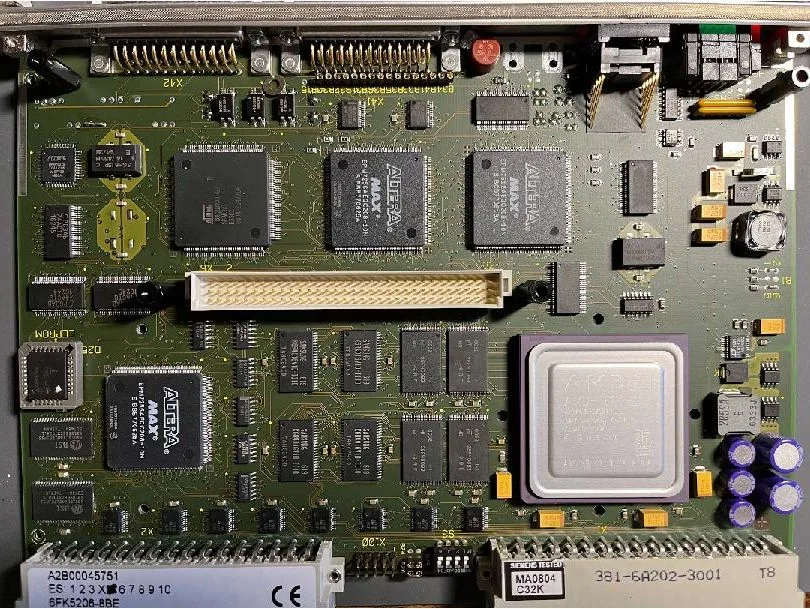

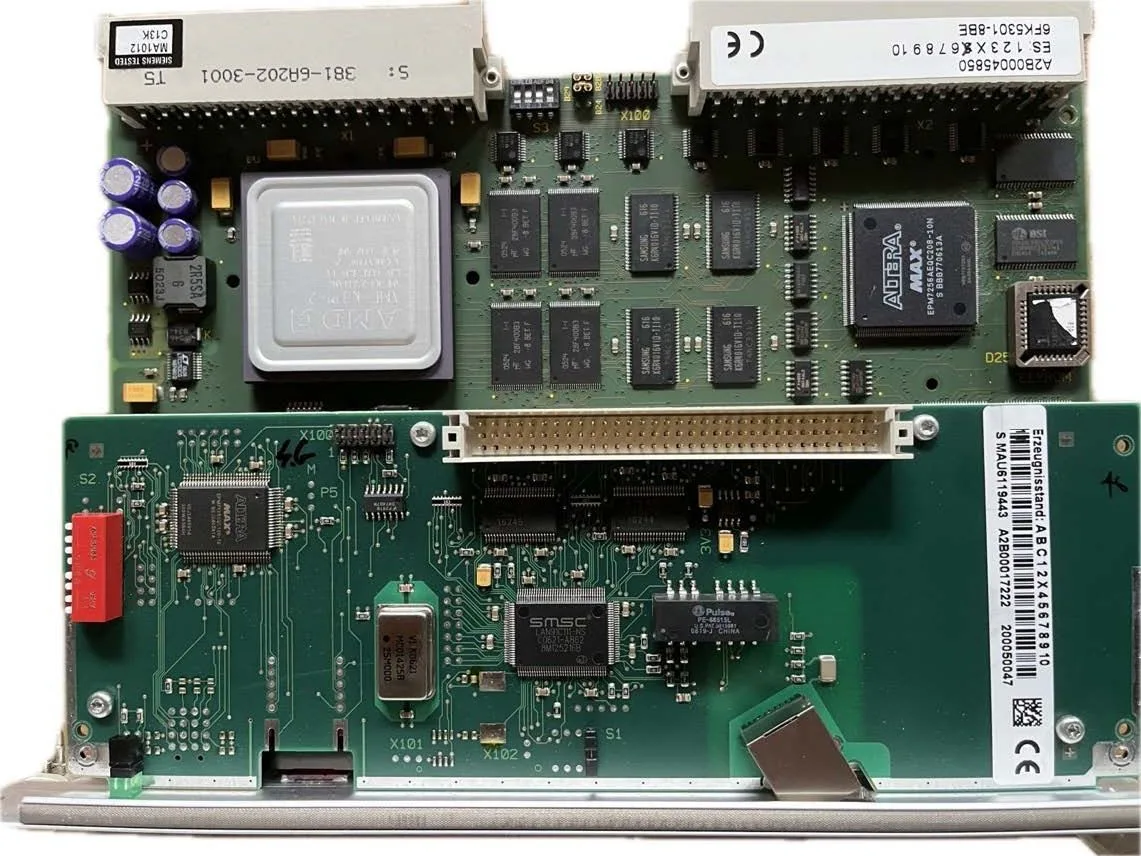

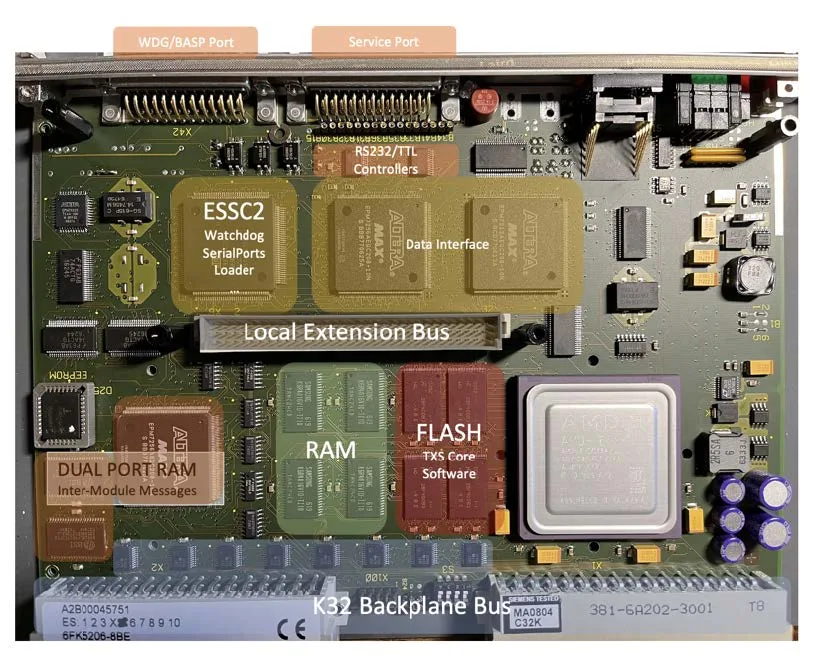

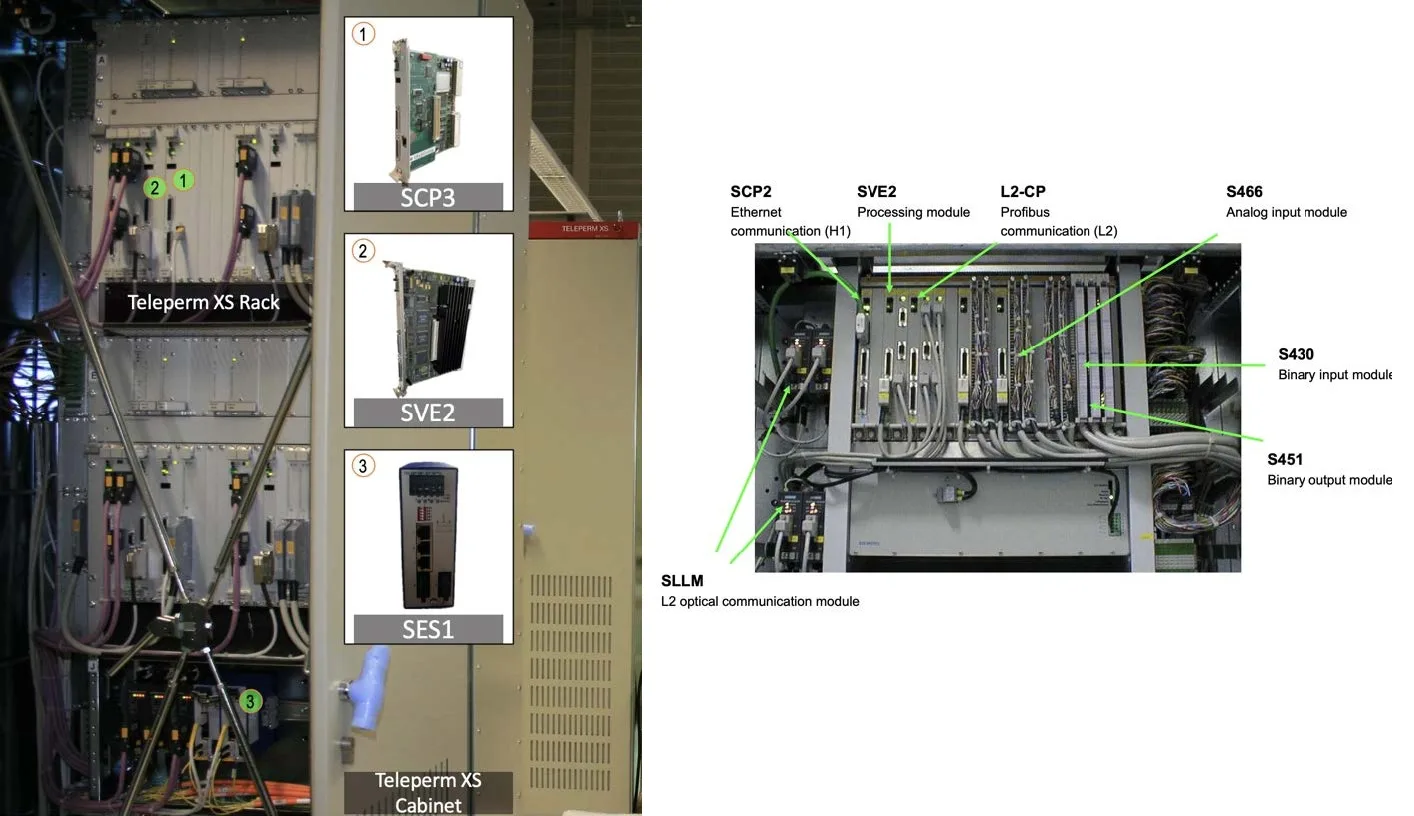

So, Ruben received the package. Inside is a shiny factory SVE2 module (general purpose processor) and SCP3 (communication module). These are the key components of the Teleperm XS digital platform (TXT) from Framatome - a former division of Siemens, which today supplies components for dozens of reactors around the world.

As critical nuclear infrastructure equipment, decommissioned, appeared for free sale at an online auction?

Most likely, this is a consequence of the curtailment of the nuclear program in Germany. Closed nuclear power plants are decommissioning equipment, and part of it, bypassing official procedures and disposal channels, pops up on the open market.

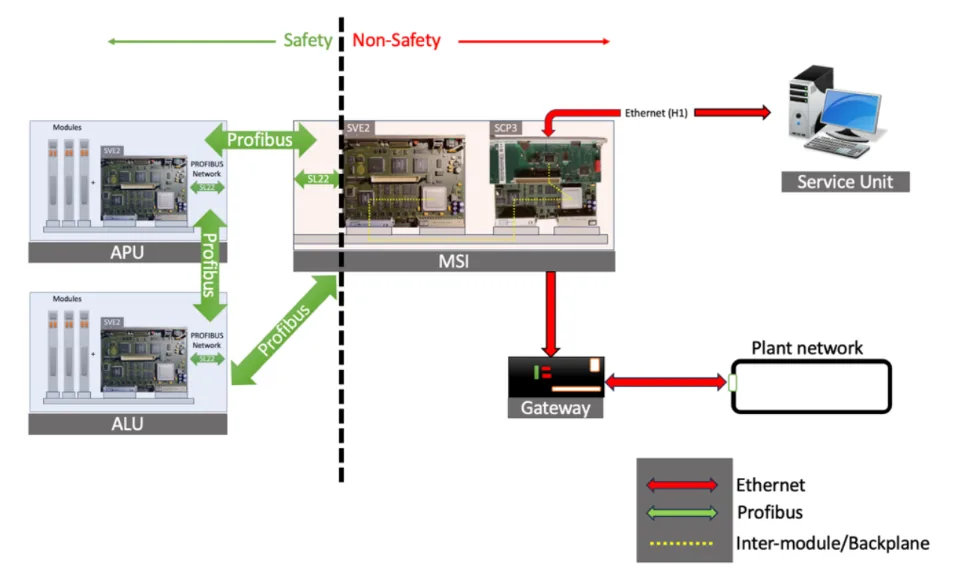

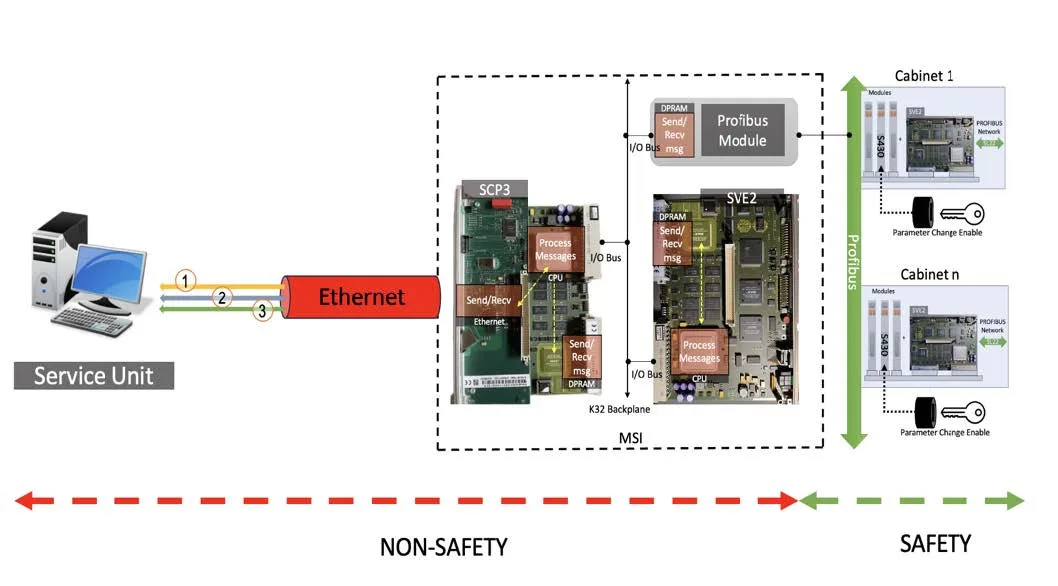

The TXS architecture is built on a modular principle.

- APU (Acquisition and Processing Unit) collect data from hundreds of sensors throughout the reactor: primary circuit pressure, the temperature, neutron flux in the core. Their task is to digitize the real world and transmit information further along the chain.

- ALU (Actuation Logic Unit) receive data from multiple APUs and make decisions based on their own voting logic. For example, if two channels out of four show dangerous values, ALU gives command to actuators: drop absorber rods into the core or start emergency cooling pumps.

- MSI (Monitoring and Service Interface) - the most critical element from a safety point of view. This is the gateway, where on one side there is a top-secret security network based on the industrial Profibus protocol, where do APUs and ALUs live?. On the other hand, a regular local network, where engineers sit with their workstations.

- They are (Service Unit) — this is a regular computer running SUSE Linux. Engineers use it to carry out diagnostics., change settings (let's say, pressure protection threshold), testing systems. The most important thing is to load new software into the APU and ALU. Service Unit is the only device, which MSI allows two-way communication with the security network.

SVE2 processors are installed in all logical blocks (APU, ALU, MSI). SCP3 is an additional communication module, which works in tandem with SVE2 to provide communications (over ethernet in MSI, по Profibus в APU/ALL).

When studying this system, its hybrid nature becomes noticeable.. On the one side, TXS - custom development specifically for nuclear power plants. On the other hand, it actively uses ready-made commercial components. For example, Hirschmann switches are used to organize the network, and a single-board computer from SBS Technologies is responsible for displaying information on operator displays.

This approach expands the potential attack surface. It's one thing to try to hack a unique closed system, documentation for which is not publicly available. And it’s quite another thing when part of the system consists of widely distributed products.

It's easy to find documentation on them, they may have known vulnerabilities. The main thing is that they can be easily purchased on eBay and easily examined in your home laboratory..

Finding holes

Any attacker will be happy to take over the Service Unit, after all, this is how you can get to the holy of holies - APU and ALU controllers, which directly control the physical processes in the reactor. However, on the way to this goal, Ruben had to overcome several barriers.

Problem #1: Empty iron

Ruben unpacked SVE2 and SCP3 modules, connected the programmer and got ready to dump the firmware for reverse engineering, but a surprise awaited him. Unfortunately (or fortunately for the rest of the world), device memory was completely empty.

Having studied the documentation, Santamarta found out, that the software is loaded into the controllers at the factory immediately before acceptance testing. Modules with eBay, Apparently, were from excess stock and were never programmed.

Ruben changed tactics. If you can't open the "brain", you need to study his “medical record” - official documentation. He started digging into public records, licensing agreements and technical specifications from the US nuclear regulator website (NRC).

It revealed, that TXS uses a simple CRC32 checksum to verify the integrity and authenticity of firmware. The problem is, that CRC32 is NOT cryptographic security. It's just a way to detect random errors in data, like parity check.

An attacker can take the standard firmware, inject malicious code into it and adjust a few bytes in the file like this, so that CRC32 remains the same. The system will accept such firmware as genuine.

But most importantly, an architectural vulnerability was found in the documents, inherent in the system design itself. To understand her, we need to talk about the most pressing issue of any security system - trust.

Problem #2: Protection by MAC address

Second barrier, which Santamarta discovered in the documentation for the American Oconee nuclear power plant, — filtering by MAC address. MSI is configured to accept commands from only one MAC address - the address of the legitimate SU. Any other computer on the same network is simply ignored.

However, for an experienced hacker, spoofing (MAC address spoofing) doesn't present any difficulty. Such a barrier will only stop the most lazy and incompetent. For a serious hacker group, this is not even a speed bump - just a marking on the asphalt. But there is one more obstacle - a physical key.

Problem #3: Key, which is not the key

And now we come to the most interesting part. US nuclear regulator (NRC) - the organization is extremely serious and conservative. In one of the key guidance documents, known as Staff Position 10, the regulator puts forward a strict requirement: transferring security systems into programming or testing mode must be implemented in hardware.

The engineer must go to the equipment cabinet, insert physical key, turn it - and this turn shouldphysically break the electrical circuit. Create an air gap between the ALU and the rest of the world.

Let's take a step back and look at the infamous Trisis malware (aka Triton or HatMan), which in 2017 attacked a petrochemical plant in Saudi Arabia. Trisis was aimed at Schneider Electric's Triconex industrial safety platform. This platform, By the way, also NRC certified for American nuclear power plants - a direct analogue of Teleperm XS.

Triconex controllers also had a key for switching modes («Run», «Program», «Stop»). The investigation showed: the key position was just a software flag. No physical circuit break. Trisis malware, hitting the controller, could remotely execute commands regardless of the key position.

How are things going with this in TXS?? Very similar. Studying piles of documents on licensing of the Oconee nuclear power plant, Santamarta found a way to bypass key protection.

Turning the key in the Teleperm XS cabinet does not directly change the operating mode of the system. It only sets one bit (logical one) on the discrete input board. This bit in system logic is called “permissive” - permission. It signals the processor: "Attention, Now the Service Unit will talk to you, he can be trusted".

The very command to change the mode (go to “Test” or “Diagnostics”) comes later on the network, from the same SU. The ALU/APU processor logic performs a simple check: “The command has come to change the regime. Looking at bit resolution. Exhibited? Okay, we carry out".

Thus, if the malware is already embedded in the ALU or APU, it can completely ignore checking this bit. The signal from the key does not exist for him. What if the malware sits on SU, he just has to wait, when the engineer turns the key for scheduled work (sensor calibration), and at this moment do your dirty deeds.

The key turns into a trigger.

Window of opportunity

Now, when we know how, the question remains - when? At what point can an attacker infect a system?? In his research, Santamarta identifies two scenarios.

Planned refueling

Once every one and a half to two years, the reactor is shut down for several weeks to replace part of the nuclear fuel - a grandiose event. They arrive at the station before 2 thousands of additional workers and contractors from dozens of companies. The security perimeter is expanding, control weakens.

In this turmoil, it is much easier to attack through an insider or a compromised contractor employee. Open the equipment cabinet, which is usually under strict control, connect an infected device to the Service Unit - in the chaos around you, this becomes possible.

Seamless connection

Regulators and nuclear power plant operators are still arguing, whether the Service Unit must be connected to the security network at all times. On the one hand, there is a complete picture of the system state in real time. On the other hand, there is a continuous attack vector.

At some modern nuclear power plants (Flamanville 3 in France, Olkiluoto 3 in Finland) SU is always connected. This means, that the attacker does not even need to wait for fuel refueling. The main thing is to find a loophole into the local network.

Simulating a disaster. "Cyber Three Mile Island"

The picture has emerged. We have a goal (Service Unit), way to bypass the first line of defense (spoofing the MAC address) and understanding, how to neutralize the main trump card - the physical key, which turned out to be a software imitation.

Let's put it all together and see, what a realistic cyber attack on a nuclear power plant might look like. Santamarta doesn't call this scenario "Cyber Chernobyl", and "Cyber Three Mile Island" - and this is much more accurate.

Why exactly this analogy?? The Chernobyl nuclear power plant was a different type of reactor (RBMK) with a positive coefficient of reactivity - when water boiled it accelerated, but didn't slow down.

The accident at the Three Mile Island nuclear power plant in the USA 1979 occurred in a PWR reactor, the same, like modern nuclear power plants. It started with a failed valve and loss of coolant. https://embedd.srv.habr.com/iframe/68c96931af3a39ea32bc0b8b

Ideal target

Santamarta chose the scenario of a small coolant leak (Small Loss-of-Coolant Accident, SLOCA) not by chance. This is the optimal attack for several reasons.

Firstly, this has happened before. Three Mile Island showed, that even a small leak can lead to a core meltdown, if security systems are not working properly. This is the only serious accident on a modern PWR in history - the perfect “template” for a cyber attack.

Secondly, Pressure compensator safety valves are controlled by digital systems, and opening the valves can be done programmatically. This attack creates a leak, which initially looks like normal operation of safety valves.

The third factor is perfect timing.. Unlike instantaneous accidents, SLOCA is developing quite slowly, so that the malware has time to block emergency response systems. At the same time quite quickly, so that operators do not have time to fully assess the situation and take the right measures.

Finally, psychological factor is triggered. Operators are accustomed to the safety valves being activated - this is a normal safety function.. Precious time is lost on diagnostics.

Step 1: Infection

It all starts during a scheduled refueling. A hypothetical attacker, through a compromised contractor or insider, gains access to the Service Unit. During routine maintenance, when the engineer inserts and turns the key to change the settings, Malware exploits this "window of trust".

The malware overwrites the firmware on all ALU and APU controllers, which he can reach. The attack must be all-out, to bypass the reservation. Besides, it can compromise the gateway to manipulate data on operator consoles. Afterwards all you have to do is wait.

Step 2: Trigger Event

Malware, sitting in ALU controllers, commands the opening of two of the three safety valves on the pressure compensator.

The pressure compensator is, In fact, large tank on top of the reactor, which creates a steam “cushion”, maintaining stable pressure in the primary circuit.

Valves open on command and get stuck open. The coolant begins to leak in the form of steam from the first, the most radioactive circuit.

Step 3: Lock protection

The pressure in the system begins to drop, automation sees this. The normal reaction of the safety system is to immediately start an emergency water injection, to compensate for the leak.

But the malware in ALU blocks this command. He sees the “low pressure” signal, sees the requirement to start the pumps and simply ignores. The pumps are silent.

Operators are very worried, they see open valves (this signal goes through a hardware channel and cannot be faked) and catastrophically falling pressure. They are trying to start the high pressure pumps themselves.

This is where the PACS priority system comes into play.. It's built like this, what are the commands from the protection system (where does the malware sit?) have higher priority over operator commands. Any attempt to close the valve or turn on the pump is immediately canceled by the malware. The security system begins to work against its creators.

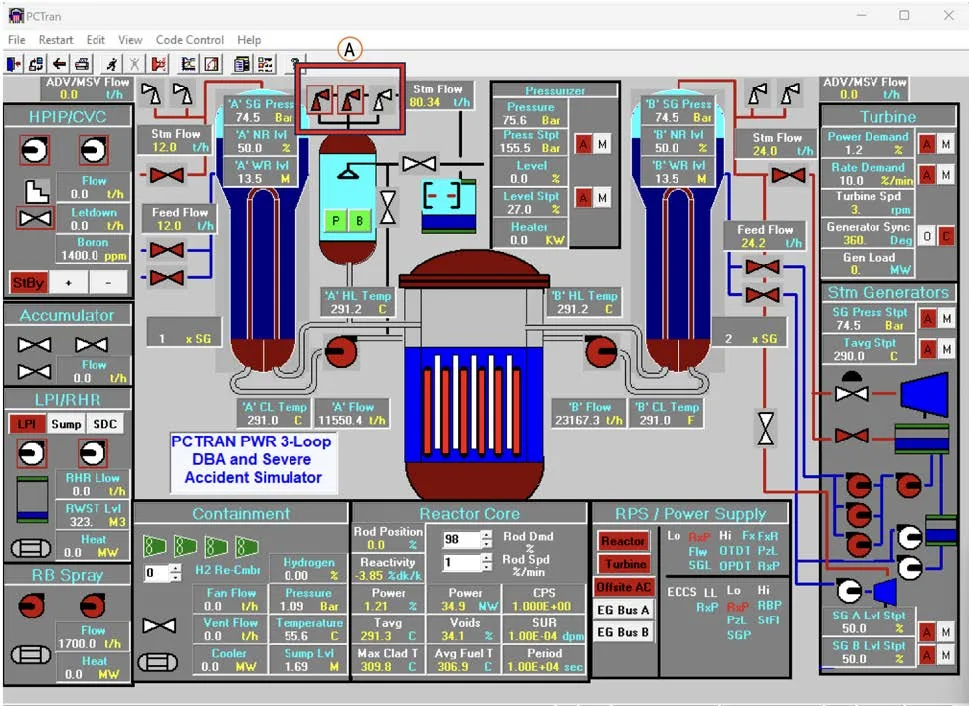

Simulation in PCTran: 49 minutes before the accident

Santamarta ran this scenario in PCTran, a professional nuclear power plant accident simulator., which is used by regulators and station operators around the world. The results were scary.

+69 seconds: The pressure in the primary circuit drops so much, that the reactor is automatically shut down. Absorber rods are lowered into the core, the chain reaction stops. But the fuel is still very hot and generates heat from radioactive decay. It needs to be cooled.

+98 seconds: Couple, exiting through open valves, ruptures the membranes in the steam release tank. Radioactive steam and water begin to fill the sealed reactor shell.

+520 seconds (8–9 minutes): The pressure drop and high temperature in the primary circuit create conditions for water to boil in the core. This process poses an additional threat.

The water in the primary circuit contains boric acid - a “liquid” neutron absorber. Since boric acid is non-volatile, boiling produces pure water vapor, and the concentration of boron in the water remaining in the reactor increases. Pure steam leaves the core to the upper parts of the circuit - steam generators. There it cools down, condenses and forms clusters of pure, debored water. They are a ticking time bomb.

+1500 seconds (25 minutes): The accumulation of debored water in the primary circuit reaches critical values. When will this “clean” water return to the core?, positive reactivity will be added.

+3029 seconds (49 minutes): Without emergency cooling, the water in the reactor continues to boil away. Finally, a critical moment is coming: the upper part of the core is exposed. Deprived of cooling, fuel rods begin to heat up at a catastrophic rate - hundreds of degrees per minute. This is the start of the meltdown.

At this point, the parallel development of the process of boron dilution turns an already critical situation into an almost hopeless one..

The operators' only hope of stopping the meltdown is to pump water into the reactor at any cost.. However, the system has already accumulated “plugs” of clean, debored water. An attempt to start the pumps and restore circulation will most likely lead to, that this clean water will be injected into the hot core.

This will cause a reactivity accident on top of the thermohydraulic: sudden increase in power, which can lead to accelerated destruction of fuel rods.

Summary of consequences: four D

What do we have as a bottom line after? 49 minutes of simulation? The Cyber Three Mile Island scenario leaves a trail of four devastating consequences.:

- Disaster (Catastrophe). Although the protective shell (containment) most likely it will survive and there will be no direct release of radiation outside, the very fact of a core melt is already an accident 5 level according to the INES scale ("An accident with widespread consequences"). For comparison, Chernobyl and Fukushima are 7 level.

- Destruction (Destruction). The core is melted, reactor destroyed, cannot be restored. Losses amount to billions of dollars, and decontamination work will take decades.

- Disruption (Crash). The country's energy system is losing a powerful source of generation. This could lead to rolling blackouts and economic collapse., especially if the attack was carried out in winter during peak loads.

- Deception (Deception). The attack can be accompanied by hacking radiation monitoring systems, drawing fake peaks on charts. Combined with a real accident at a nuclear power plant, this will sow panic and distrust in the authorities, who cannot clearly explain what is happening.

Cold vulnerability analysis

It's important to understand: the described scenario is a theoretical model in ideal conditions for an attacker. In reality, the probability of success of such an operation is extremely low..

To attack, you still need to understand the firmware structure, which the researcher never received.

Besides, an attacker would have to overcome not only digital, but also physical protection. Modern reactors have a number of passive safety systems, which will work automatically under the influence of the laws of physics (For example, high pressure accumulators, injecting water when pressure drops even without a command), as well as hardware locks, which are not controlled by the software.

Nevertheless, The very existence of this possibility underscores the need for continued improvements in security measures even in such a highly secure industry., like nuclear energy.

That's not the point, that the Teleperm XS platform is bad. The thing is, that she, like any complex system, is a product of its era and compromises.

Using a simple CRC32 to check the integrity and authenticity of firmware in 2024 year - archaism, and the story with the “key”, which is not the key" is the clearest example of that, as a regulatory requirement, implemented formally, not in spirit, turns into a security theater.

Lessons for the new generation

Now giant nuclear power plants are being replaced by Small Modular Reactors (SMRs). They are cheaper, they can be built faster and used in a variety of conditions - from powering remote cities to powering data centers.

Lessons, lessons learned from similar studies, vital to consider when designing these reactors. The cost of error here is extremely high. Such people, as Ruben Santamarta, point out weaknesses for the wrong reasons, to spread fear, and to make the system stronger. Our task is to listen to them very carefully. Because the alternative is when we learn about vulnerabilities not from scientific articles, and from news reports.

138 pages of original researchavailable for download on Ruben Santamarta's website.

Discover more from VirusNet

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.